St. Mary Magdalene Was Not a Prostitute

Today is the Feast of St. Mary Magdalene. Let's set the record straight.

JULY 22, 2025 — In the Western mind, St. Mary Magdelene is often cast as the penitent prostitute, a woman of ill repute redeemed by Christ’s mercy… or worse. It’s a compelling story, dripping with the drama of sin and salvation. But it’s not the truth.

Let’s begin with the Gospels, the bedrock of Christian truth. Mary Magdalene appears in all four, most prominently in John, where she is the first to encounter the risen Christ (John 20:11–18). She is described as a devoted follower, one of the women who supported Jesus’ ministry (Luke 8:1–3). Luke tells us she was delivered from “seven demons” (Luke 8:2). This detail speaks to spiritual affliction, not moral failing. Indeed, nowhere in the Old Testament is demonic possession described as a punishment for, or consequence of, sins of lust—or any other sin, for that matter.

Likewise, nowhere in the New Testament is she identified as a prostitute. This idea stems from a Latin habit of conflating Mary Magdalene with the unnamed “sinful woman” who anoints Jesus’ feet in Luke 7:36–50. That woman, often assumed to be a prostitute due to the cultural context of her “sinful” reputation, is never named. Yet, by the sixth century, Pope Saint Gregory the Great cemented this identification in a homily, and the West ran with it.

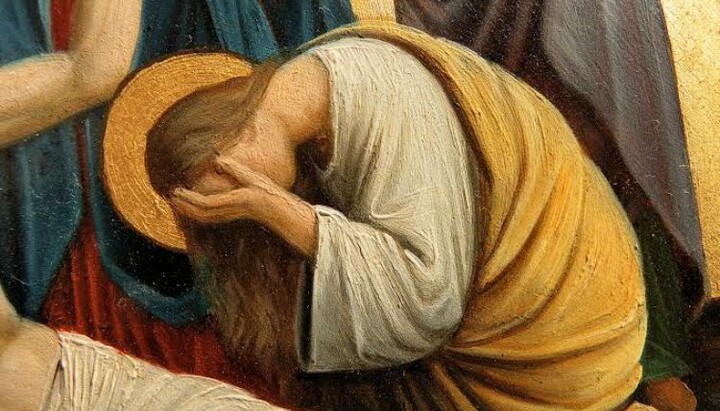

The Orthodox Church, however, never bought into this narrative. In the East, Mary Magdalene is venerated as a saint of unimpeachable devotion, the “Apostle to the Apostles,” who carried the good news of the Resurrection to the disciples. The Synaxarion, the Orthodox Church’s collection of saints’ lives, makes no mention of prostitution. Instead, it emphasizes her role as a Myrrh-Bearer: one of the women who went to anoint Christ’s body at the tomb. Her hymns in the Orthodox liturgy sing of her fidelity, her courage, and her love for the Savior. The idea that she was a fallen woman redeemed by grace is absent from the Eastern tradition, which sees her as a model of holiness, not a cautionary tale of sin.

So, where did the prostitute myth come from? It’s a classic case of eisegesis—reading into the text what isn’t there. The Latin Church, in its zeal to craft a narrative of redemption, stitched together disparate threads: the sinful woman of Luke 7, Mary of Bethany (who anoints Jesus in John 12), and Mary Magdalene. The result was a composite figure, a penitent harlot whose tears and perfume became symbols of contrition. It’s a beautiful story, but beauty doesn’t make it true. Indeed, it imputes to this great saint a crime that she never committed.

The fact that the Orthodox Church never “developed” this “tradition” is proof in itself that the Latin concept is wrong. After all, how could it be that the Church in Jerusalem—whose first members were Mary Magdelene’s friends and family—had forgotten her sins, but they had somehow been transmitted secretly to the West, only to resurface in the 6th century?

Thank God, the Orthodox Church has a long and clear memory. They kept the figures distinct, recognizing that the Gospels don’t warrant such a conflation. The Eastern Fathers, like St. John Chrysostom, speak of Mary Magdalene’s devotion without a hint of scandalous backstory.

The “seven demons” mentioned in Luke 8:2 are often cited as evidence of a sordid past, but this is a leap. As we said, in the ancient world, demonic possession was associated with spiritual or physical ailments—not necessarily moral depravity. The number seven, symbolic of completeness, suggests a profound affliction, perhaps mental or spiritual torment. To equate this with prostitution is to impose a modern lens on an ancient text. The Gospels are silent on the nature of her demons, and silence demands humility, not speculation.

This mischaracterization matters because it distorts our understanding of sanctity. Mary Magdalene stood at the Cross when the apostles fled (John 19:25). She lingered at the tomb when hope seemed lost (John 20:11). Her encounter with the risen Lord is one of the most intimate moments in Scripture: “Mary,” He says, and she replies, “Rabboni!” (John 20:16). This is not the profile of a reformed sinner but of a woman wholly devoted to her Lord, a prototype of Christian discipleship.

The prostitute myth also risks reducing Mary Magdalene to a trope. She becomes a symbol, a morality play, rather than a person. The Orthodox tradition preserves her humanity, portraying her as a woman of courage and faith. This aligns with the broader Orthodox ethos, which resists sensationalism in favor of sober reverence. The West’s fascination with dramatic conversion stories—while somtimes pastorally useful—can obscure the quieter, no less profound, witness of those who simply follow Christ without a lurid backstory.

To be fair, the Western tradition has produced beautiful art and devotion inspired by the penitent Magdalene. Think of Caravaggio’s haunting paintings or the medieval legends of her ascetic life in the desert. But beauty must serve truth, not supplant it. The Orthodox Church, with its insistence on fidelity to Scripture and tradition, offers a necessary corrective. Mary Magdalene was not a prostitute. She was a disciple, a witness, a saint. Her story doesn’t need embellishment to inspire. The truth is powerful enough as it is.

In an age that loves to sensationalize, the Orthodox witness to Mary Magdalene calls us back to the Gospels’ plain truth. She was a woman who loved Christ, who bore the myrrh of devotion, and who saw the empty tomb first. Let’s honor her as she is, not as we’ve imagined her to be.