The Catholic Saint Who Almost Became Orthodox

Josemaria Escriva, the founder of Opus Dei, was dismayed by the liberalizing "reforms" that followed Vatican II. In 1967, he traveled to Greece to explore the possibility of becoming Orthodox. In the end, he decided to stay put and pursue a "conservative revolution" within the Roman Church. Then, last week, Pope Leo XIV's recent move to break up Opus Dei. It's a lesson in the futility of Catholic "traditionalism"—and the need for Holy Orthodoxy.

Last week, Pope Leo XIV announced that he would break up the Personal Prelature of Opus Dei.

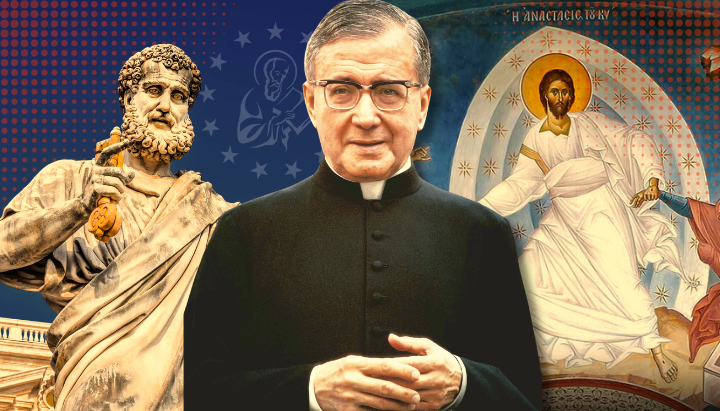

Founded in 1928 by Josemaria Escriva, the name Opus Dei means “the Work of God.” It was formed to promote a concept that was central to Escriva’s vision: the sanctification of ordinary life. However, it quickly became a subject of controversy and even conspiracy. Josemaria Escriva was canonized in 2002—an event that generated a great deal of controversy.

Opus Dei is best known for its “appearance” in Dan Brown’s The Da Vinci Code. One of the main antagonists, Silas, is an albino monk. He wears a cilice (a barbed strap worn around the thigh) and whips himself with a discipline (a scourge made out of knotted rope). Silias is said to be a member of Opus Dei, and serves as an assassin for the order’s patrons: a small group of ultra-conservative cardinals based in Rome.

Like most of Brown’s work, it’s thrilling rubbish. First of all, Opus Dei doesn’t have monks. Some members do use a cilice, but only for short periods while praying; they don’t go around in them all the time. And, to the best of my knowledge, they don’t whip themselves. Brown did get one thing right, however: Opus Dei is generally identified with the conservative wing of the Catholic Church.

It became so powerful, in part, because its leaders were very good at forging alliances with powerful actors. Escriva was very friendly with the Franco regime in his native Spain. His successors, meanwhile, aligned closely with Pope John Paul II.

Opus Dei has been accused of elitism, targeting wealthy laymen to become numeraries (who are celibate and live in Opus Dei housing) and supernumeraries (who can be married). In recent years, the group has also been accused of heinous crimes, including human trafficking.

How did Opus Dei get away with so much for so long? Much of it has to do with the group’s unique status as a personal prelature. Hence, Leo’s push to restructure “the Work.” (See this UOJ explainer by for more information.)

Now, from Opus Dei’s perspective, it could be worse. The group could have been suppressed altogether—a decision that would have delighted many. Still, the restructuring wrecks Josemaría Escriva’s vision for Opus Dei.

Not many Catholics realize this, but Opus Dei was founded as a reformist movement. Simply put, Escriva created "the Work" for many of the same reasons that the Second Vatican Council was convened three decades later. He saw that the Catholic Church was committing spiritual suicide. Rome had been broken by a series of disastrous events: the Protestant Reformation, the French Revolution, etc. Generations of popes had fought to retain their moral and political authority, with varying degrees of success. Overall, however, they were unsuccessful. The situation looked grim.

Escriva sought to renew the Church by emphasizing everyday holiness: a recommitment to personal prayer, fasting, and the life of virtue. This, of course, is a much more “conservative” vision than the one pursued by the Second Vatican Council, which inaugurated a campaign of “modernization” in the Church—theological, spiritual, and liturgical.

The Second Vatican Council convened in 1962, when Escriva was sixty years old. This came as a blow to Escriva—who, again, had aligned himself with the Nationalists during the Spanish Civil War. When the Novus Ordo Missae was promulgated in 1969, he refused to learn it, and continued to celebrate the old Latin Mass.

Of course, this is not how Opus Dei's apologists tell the story. One individual who has tried to run interference is Dr. Giuseppe Soria, his personal physician. “Josemaria was always first and foremost obedient,” Soria insists. Of course he would have loved to celebrate the Novus Ordo! But he had certain… impediments. Soria goes on to say:

He could not read the faded print in the new edition of the Roman Missal. He had cataracts and found it difficult and painful to read the poor quality typeset. Also, the saint had experienced certain mystical moments associated with particular words, sentences, and structural parts of the [Latin Mass]. Such moments had been a part of his spiritual life since boyhood and through his priesthood. In having to celebrate the Mass of Paul VI, the saint would have been cut off from this.

Of course, in the mid-1960s, the Latin Mass had been part of every Catholic’s “spiritual life” since boyhood (or girlhood). Yet few priests—and fewer laymen—were allowed to continue enjoying the Latin Mass. In fact, some traditionalists were so afraid of being “cut off” from their liturgical heritage that they broke with Rome completely. The most prominent example is Abp. Marcel Lefebvre and the Society of St. Pius X.

So, allowing Escriva to continue saying the Latin Mass was no small concession on Rome’s part. Clearly, there was more at stake for Escriva than straining his eyes.

In fact, Vladimir Feltzmann—a former member of Opus Dei who served as the founder’s personal assistant—claims that, shortly after Vatican II, Escriva traveled to Constantinople and sought to join the Orthodox Church. According to a 2010 article from Newsweek:

Feltzman claims that Escriva was so despondent over the outcome of Vatican Council II that he and his successor, Bishop Alvaro del Portillo, “went to Greece in 1967 to see if he could bring Opus Dei into the Greek Orthodox Church. Escriva thought the [Catholic] Church was a shambles and that the Orthodox might be the salvation of himself and of Opus Dei as the faithful remnant”.

Again, Opus Dei has worked hard to doctor the record. They rejected Fletzman’s testimony, insisting that Escriva traveled to Greece in order to explore the possibility of establishing an Opus Dei presence. But that’s patently absurd. Opus Dei had little presence outside of non-Catholic countries. Exceptions were made only for Western European states with large Catholic minorities. For instance, “the Work” expanded into the United Kingdom in 1954, when were about 3.5 million Catholics in England. By contrast, there were only 50,000 in Greece when Escriva scouted the country in 1967. Not exactly fertile ground.

I’ve heard that Escriva’s plans were dashed when he met with the Greek bishops. They told Escriva that, of course, he and his followers would be welcome to convert—but they couldn’t bring Opus Dei with them. The Orthodox Church doesn’t have religious orders, the bishops explained. Priests are priests, monks are monks, and that’s all there is to it. Escriva returned to Rome disappointed, but not empty-handed: he brought Pope Paul VI a number of Byzantine icons as a token of his loyalty.

The life of Josemaria Escriva makes for a fascinating story. It’s also a cautionary tale. He clearly recognized the spiritual rot that had consumed the West. He also recognized—at least on some level—that the Orthodox Church was the only solution. Yet he couldn’t let go of his own vision for how to “reform” the West.

At the time, the “Escrivan” model seemed like it had a fighting chance. Now, the moment has well and truly passed.

Today, so many Catholics are drawn to Orthodox Christianity. And yet so many refuse to convert, preferring (like Escriva) to promote their own "conservative revolution" in the Catholic Church. For some, it’s some reactionary ideology: traditionalism, illiberalism, etc. Others, like uniates and papal minimalists, will “borrow” bits of Orthodoxy that they like and leave the ones they don’t.

All of these schemes will fail. Because the Orthodox Church is the Rock of St. Peter. Any house built on that rock will stand strong. Everything else is built on sand and will be washed away with the tide.