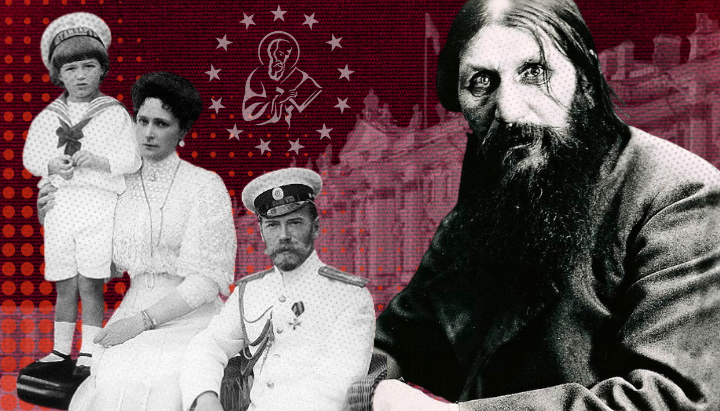

Does Rasputin Discredit the Romanovs?

Nicholas, Alexandra, and their children resisted the “spirit of the age” to their final breath. They chose to die rather than forsake their duty to God and their country. That is what makes them saints: their fidelity, holiness, and love. Rasputin’s shadow may linger, but it doesn’t eclipse their light.

In my recent article “Was Rasputin a Saint?”, I argued that while the most egregious accusations leveled against the “holy peasant” are patently false, he was not a genuine mystic or faith healer and was undoubtedly both an alcoholic and a womanizer.

My conclusion was not universally welcome.

The most common objection was that, by casting doubt on Rasputin, I also cast doubt on the discernment—even the sanctity—of the Romanovs themselves. After all, Tsar Nicholas II and Tsaritsa Alexandra placed immense trust in him. They granted him unprecedented access to their court and their family. My critique, therefore, strikes at the very heart of the Romanovs’ legacy, particularly since the Russian Orthodox Church canonized them as passion-bearers in 2000. Or so the critics say.

This concern is far from new. It echoes the very debates that unfolded within the Moscow Patriarchate during the canonization process. Some hierarchs and theologians opposed raising the Romanovs to the altars precisely because they wished to avoid “canonizing” the late-tsarist regime along with them. The empire under Nicholas II was marred by political missteps, social unrest, and genuine policy failures. By canonizing the family, we risk whitewashing these flaws.

And few errors loom larger in popular memory than their association with Rasputin, whose influence symbolized the decadence and superstition that allegedly hastened the dynasty’s fall.

For what it’s worth, my wife and I have a deep devotion to the Royal Martyrs. We’re doing our best to pass that devotion to our daughters: we put an icon of the Romanovs in the little icon corner I built in their bedroom. Nicholas, Alexandra and their children are right below Christ and the Theotokos.

And I’ll say this: so far as Rasputin is concerned, the Romanovs are guilty of nothing more than being taken in by a faith-healer during a time of desperation. This wasn’t an isolated lapse; the family had a history of seeking solace from unconventional spiritual figures. Consider their earlier friendship with “Monsieur Philippe,” a French occultist and self-styled healer who influenced Nicholas and Alexandra in the early 1900s. Like Rasputin, he entered their lives at a moment of deep vulnerability: Alexandra was unable to conceive a son. Such associations reflect a certain (deeply human) weakness on the Romanovs’ part—not any malice or faithlessness.

This vulnerability is entirely understandable when viewed through the lens of their personal tragedy. When she did finally have a boy—Tsarevich Alexei—he was found to suffer from hemophilia. Alexei’s condition caused excruciating pain. He lived his entire life on the verge of an unhappy and untimely death. Naturally, this left his family in constant anguish as well.

Rasputin entered their lives as a beacon of hope. And he did appear to alleviate Alexei’s suffering on multiple occasions. As I detailed in my previous article, this relief can often be explained by natural means; however, this explanation was unavailable to Russians in the early 20th century.

For instance, Rasputin suggested that Alexei’s doctors stop “bothering” him when he was suffering an attack. This indirectly prevented them from administering aspirin to the boy. At the time, aspirin was viewed as a cure-all; we now know that it’s a blood thinner and should never be given to a hemophiliac, especially when he or she is in the throes of a “bleeding spell.” exacerbated hemophilia. So, from the Romanovs’ perspective, Rasputin’s influence on their son would have seemed miraculous.

Complicating matters further, several contemporary saints questioned Rasputin’s sanctity. For instance, St. Elizabeth the New Martyr viewed him with deep suspicion, decrying his influence as unholy and urging her sister (the Tsaristsa) to send him away forever. In the end, Rasputin was assassinated by fanatical monarchists who wished to protect the Royal Family from this madman; St. Elizabeth celebrated the assassins and was relieved by Rasputin’s death. Other saints who opposed Rasputin include Benjamin of Petrograd, Mardarije of Libertyville, and Hermogenes of Tobolsk.

Rasputin’s defenders often counter that these saints didn’t know him as intimately as the Romanovs did, suggesting their judgments were based on rumors rather than personal interaction. This is patently untrue in the case of a man like Hermogenes. Nevertheless, this defense raises its own thorny issues. After all, what kind of saint hastily judges a man she doesn’t know and then gloats over his murder?

Of course, this doesn’t prove Rasputin’s guilt. My point is that, if criticizing Rasputin call into question the Romanovs’ sanctity, then defending Rasputin calls into question St. Elizabeth’s.

At the end of the day, the Romanovs were canonized for their infallible character judgment. No: they were canonized for the depth of their faith and their holy death at the hands of godless communists. The Church recognized them as passion-bearers—those who faced death with Christ-like forgiveness and endurance.

Nicholas, Alexandra, and their children had everything to lose: unimaginable wealth, absolute power, and, most heartbreakingly, their close-knit family. Yet, amid imprisonment, deprivation, and execution, they stood firm in the Orthodox Faith. Diaries from their final days reveal that they devoted themselves to prayer and reading the Holy Scriptures, quietly resigned to the will of God.

This is also why the Church did not canonize Rasputin. Again, this came up when the Holy Synod of the Russian Orthodox Church (under His Holiness Patr. Alexei II, of blessed memory) was weighing the possibility of canonizing the Romanovs Ultimately, the Synod decided to separate the family’s sanctity from Rasputin’s influence. They canonized the Romanovs but not Rasputin.

This was the right choice. While he professed Orthodoxy and aided the Romanovs in their hour of need, his life lacked the consistent holiness required for sainthood. His excesses outweighed his virtues; his influence, even if well-intentioned at times, contributed to the regime’s instability.

So, does Rasputin discredit the Romanovs? Not at all. Their only “sin” in this regard was that suffering—suffering on a scale unimaginable to most human beings—clouded their judgment enough that they fell for a (rather convincing!) false mystic.

The important thing is that Nicholas, Alexandra, and their children resisted the “spirit of the age” to their final breath. They chose to die rather than forsake their duty to God and their country. That is what makes them saints: their fidelity, holiness, and love. Rasputin’s shadow may linger, but it doesn’t eclipse their light.